Share:

A resilient city is an urban area capable of absorbing, adapting to, and recovering from shocks and long-term stresses — from acute disasters such as storms, floods, and landslides, to chronic pressures such as rapid urbanization, ecosystem degradation, and supply-chain vulnerabilities.

1. Definition of a Resilient City

A resilient city is an urban area capable of absorbing, adapting to, and recovering from shocks and long-term stresses — from acute disasters such as storms, floods, and landslides, to chronic pressures such as rapid urbanization, ecosystem degradation, and supply-chain vulnerabilities.

The concept is not measured solely by a city’s ability to “withstand” impacts, but also by its capacity to learn, transform, and maintain essential functions for its residents.

2. A Practical Implementation Pathway Must Consider All Risks

.jpg)

Figure 1. Infographic illustrating typical risks faced by port cities, source: IPCC

When discussing climate risk, people often think only of physical hazards such as stronger storms, extreme rainfall, or sea-level rise. However, according to the IPCC, this is only part of the picture. To properly assess risk, three additional determinants must be examined:

1. Vulnerability of communities

This factor is strongly shaped by socio-economic conditions: poverty, inequality, informal housing, and social exclusion. Vulnerable groups consistently suffer the most severe impacts in any disaster.

2. Adaptive capacity and ability to recover

A climate hazard becomes a disaster only when communities cannot cope or recover. This is directly tied to:

• people’s behavior,

• governance and institutional capacity,

• availability of capital and long-term investment.

3. Exposure to hazards

Geographical location, pace of urbanization, and the expansion of settlements into low-lying or coastal zones all increase exposure — even when the frequency of hazards does not rise significantly.

These additional factors are particularly relevant to Asia — home to many megacities that grow rapidly yet face deep inequality. Uncontrolled urban expansion and informal construction leave large populations fully exposed to storms, floods, and tidal surges.

.jpg)

Figure 2. Map of Asian countries affected by sea-level rise; Vietnam is among the most vulnerable. Source: UN-Habitat

Kavita Sinha — Director of the Private Sector Facility at the Green Climate Fund (GCF) — notes:

“Coastal cities in Asia are not prepared for a scenario of warming above 2°C. They are acting, but their resources are insufficient.”

She further emphasizes that climate resilience is not only a climate issue, but a determinant of economic competitiveness:

“Resilient cities will attract capital and economic activity. Cities that fail to act will fall behind.”

.png)

Figure 3. Kavita Sinha speaking at the 15th World Forestry Congress

3. Core Principles for Making Urban Infrastructure Climate-Resilient

To move from concepts to action, cities typically employ a combination of engineering, design, and governance measures. The key strategic groups below are distilled from global guidelines (World Bank, OECD, IPCC, UN-Habitat):

a) Design infrastructure based on lifecycle and climate scenarios

• Develop risk maps and scenario models (flood maps, sea-level rise projections, extreme rainfall bands) to set requirements for elevation, drainage capacity, and structural loads — rather than relying on historical standards.

b) Upgrade systems using both “hard” and “soft” measures

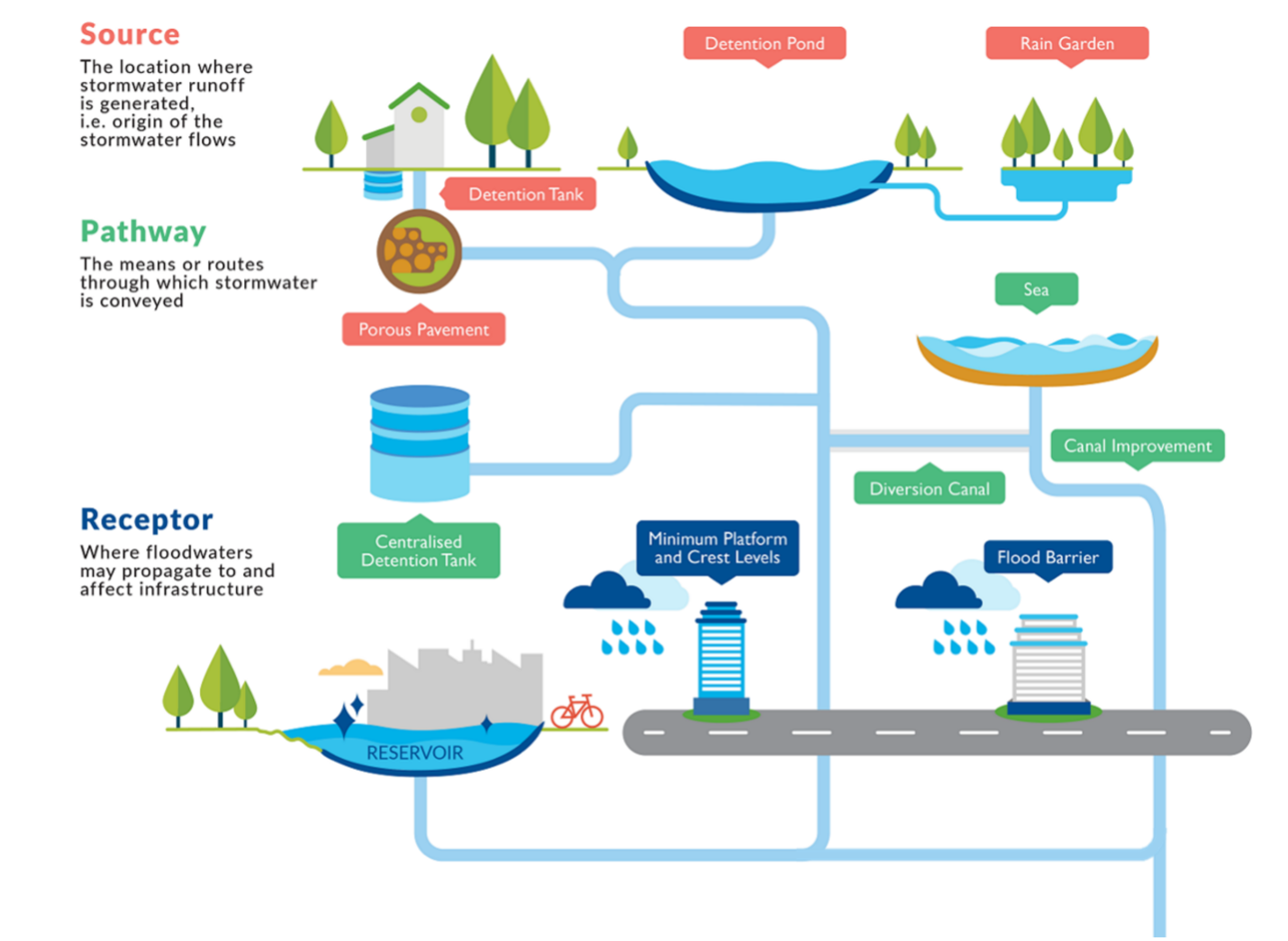

Figure 4. Diagram of elements required for effective drainage, source: Singapore’s National Water Agency

• Hard engineering: sea walls, large culverts, pumping stations, elevated roads, reinforced bridges.

• Nature-based solutions: restored wetlands, mangrove forests, retention parks, and detention lakes to absorb stormwater and reduce pressure on drainage systems. These solutions also provide co-benefits such as biodiversity, urban cooling, and enhanced public space.

c) Integrate governance, data, and finance

• Early-warning systems, emergency-fund mechanisms, updated design standards, and PPP financing models for resilient infrastructure.

• Investments should consider Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) rather than upfront cost alone.

d) Ensure flexibility and redundancy

• Design modular systems and service redundancies so that if one road, power line, or water line fails, the network continues functioning.

e) Put people at the center — especially vulnerable groups

• Resilience is not only technical; plans must ensure that vulnerable residents can access early warnings, social protection, and post-event support.

China has been piloting the “sponge city” model — where parks, lakes, and permeable systems absorb rainfall into underground reservoirs. Over the past decade, major coastal cities such as Tianjin, Xiamen, and Shanghai have been restructured to incorporate this model.

In Sanya, the Dong’an Wetland Park is a notable example where sponge-city design successfully manages stormwater flooding in a coastal urban environment.

.jpg)

Figure 5. Dong'an Wetland Park in Sanya, applying sponge-city principles to better manage urban floodwater. Image: Turenscape.

The sponge-city approach not only reduces flood risk but also cools cities during heatwaves, while stored water can be filtered and reused more easily than wastewater. However, high upfront costs and recent extreme flood events that exceeded system capacity have slowed adoption. GCF researchers note that better planning, city-specific customization, and clearer legal mandates are needed to demonstrate broader public-health and socio-economic benefits.

Experts at the GCF further stress:

“The barriers are not technical — they are social, institutional, and political. To win support, sponge-city models must show clear economic and social returns.”

4. Strengthening Financing for Urban Resilience Projects

Despite escalating climate risks, adaptation finance still attracts limited private-sector interest. Infrastructure such as sea walls or drainage systems rarely generates direct revenue, unlike mitigation projects (e.g., renewable energy).

Moreover, avoided losses and indirect benefits are rarely captured in traditional economic models. In developing countries, public budgets are also strained by health, social welfare, and defense, leaving limited resources for adaptation.

Some countries are exploring new solutions. China is piloting land value capture, where the government recovers part of the increased land value around areas upgraded with public infrastructure and reinvests it into resilience projects. Research in China also shows rising property values linked to improved air quality — helping quantify intangible benefits and enabling new forms of taxation for reinvestment.

In climate adaptation, more resilient infrastructure helps stabilize asset values against extreme weather — providing a rationale for dedicated taxes or fees supporting large-scale projects.

Multilateral development banks are also promoting blended finance, where they provide concessional capital to de-risk projects and attract private investors. The GCF has co-financed projects ranging from sanitation and transportation upgrades in Bangladesh’s informal settlements to water-supply improvements in Kiribati.

According to GCF, climate-adaptation business models are still emerging, but demand for investment in food security, water security, and climate-resilient infrastructure is rising rapidly. However, blended-finance deals remain a small share of the market. To scale up, governments must introduce clear policies, reduce regulatory risk, and foster localized financing — national green banks, municipal green bonds — to reduce currency risks and prioritize domestic needs.

The private sector is also testing mechanisms such as parametric climate insurance, which automatically pays out when weather thresholds are exceeded (e.g., excessive rainfall or high temperatures). Some rice and coffee farms in Vietnam have begun adopting such insurance.

5. Conclusion: Strategic Implications for Policymakers — Building for the Future

• Resilient cities are not a one-time solution; they require continuous investment in both physical infrastructure and governance, legal, and financial reforms.

• Effective strategies combine hard–soft solutions, local data, and social inclusion — particularly for the poor and vulnerable.

• In Southeast Asia, practical experience shows the need to balance “big solutions” (sea walls, pumping stations) with “nature-based/local solutions” (mangroves, detention lakes, urban drainage upgrades). Successful projects adopt an integrated vision — technical, economic, and social.

• Practical policies must focus on unlocking financial value to scale up resilience investments that deliver long-term societal benefits.

Sources

UN-Habitat — Guide to the City Resilience Profiling Tool

UNDRR / MCR2030 — Making Cities Resilient 2030

IPCC AR6 — Cities, Settlements and Key Infrastructure

OECD — Infrastructure for a Climate-Resilient Future (2024)

World Bank — Resilient Cities Program & Urban Infrastructure Guidance

Case studies: PUB Singapore — Marina Barrage; Jakarta NCICD; HCMC Flood-Risk Management (World Bank)

Latest news

Low-Cost Pathways to LEED Certification: A Practical Guide

This guide outlines LEED credits and prerequisites that can be achieved with little to no major material or construction cost. These strategies focus on early planning, documentation, process alignment, and smart site selection, making them especially suitable for projects seeking cost-effective sustainability outcomes.

Vietnam’s Government Policy: Reshaping the Future of the Construction Industry

The Vietnamese government is accelerating policy reforms that are poised to transform the construction industry over the next decade, balancing ambitious growth with environmental sustainability and regulatory rigor.

“Green” Imprints 2026: Trends, Evidence, and Lessons from Southeast Asia

Hanoi / Ho Chi Minh City, 2026 — The year 2026 marks another decisive phase of transformation in Vietnam’s real estate market: “green” is no longer a marketing slogan but is becoming a criterion for financial risk assessment, capital access conditions, and project operation standards.

When Voids Speak: Terrain Vague and the Cities That Resist Total Planning

Every city carries fractures within it — remnants, vacant lots, abandoned structures, and layers of surplus infrastructure that fall outside the spotlight of official planning. These are spaces out of sync with urban order, yet they unexpectedly form the city’s “underside,” where seemingly continuous structures begin to rupture.

Urban Cooling — A Sustainable Pathway Integrated into Infrastructure Planning

Vietnam is increasingly demonstrating strong commitment to reducing emissions and responding to climate change by placing “sustainable cooling” at the center of urban planning and development.

Nature in Cities: Ecological Infrastructure — Not Decoration

Urban nature isn’t a decorative layer. It cools streets, filters water, reduces floods, supports pollinators—and improves human wellbeing.

Build Green, Build with ARDOR Green